By Camryn Romph

The racial disparity of infant mortality in Kalamazoo, Michigan has recently come to the community’s attention. Statistically speaking, black babies are currently 4.5 times more likely to die before their first birthday than white babies are. In a class project, focus groups were conducted to identify certain themes that tie together many different individual cases of infant mortality. One of these themes, domestic violence, was a common factor in many of the unique stories and experiences of both women who have been affected by infant mortality, as well as Kalamazoo community health care professionals. Many of the participants, as well as other studies, suggest that there is also a racial disparity that shows the black population may also be more likely to experience domestic violence. Domestic violence in itself creates a myriad of complications and consequences, both indirect and direct, which can impact the health of a mother and an infant and, in turn, may influence the mortality of an infant. This paper seeks to contextualize domestic violence and the diverse roles and contributions it has on the racial disparity of infant mortality in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

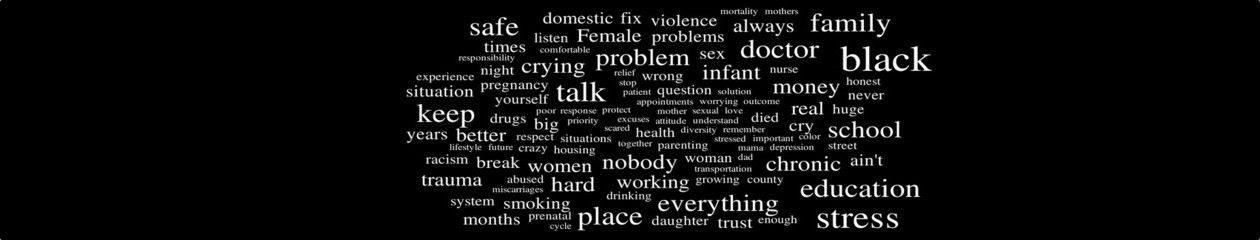

While overall infant mortality in Kalamazoo County has been improving over the past decade, the city of Kalamazoo has seen infant mortality within the black population increase almost three times the rate it was twenty years ago (McMichael, 2015). To address this disparity, Kalamazoo began a community-wide initiative to reduce the black infant mortality from its current rate of 4.5 (4.5 deaths of infants under one year per 1,000 live births in a single year) by the year 2016. Alison Geist’s Kalamazoo College class, Community and Global Health, conducted eight focus groups of Kalamazoo residents and health care workers to gain a more thorough understanding of the racial disparity seen in Kalamazoo’s infant mortality. Students further derived several themes that were consistently seen in the interviewees’ experiences. One of these themes, domestic violence, was recognized by many of the Kalamazoo residents as being a prominent contributor to infant mortality, specifically in black women. The influence of domestic violence on the issue of black infant mortality in Kalamazoo is analyzed in this paper using local data and quotations from the focus groups.

Many of the focus group participants—both Kalamazoo residents and health care workers—referred to the impact that violence during one’s childhood has on a woman throughout adolescence and adulthood, specifically for a woman who experiences the loss of a fetus or an infant. For example, one black Kalamazoo resident said,

We [black people] have more challenges as far as where we come from. Our parents have been some of them alcoholics, some of them drug users, some of them in the domestic violence program, which stresses out all of us and, you know, we try to protect ourselves cuz from us not wanting to be like our parents. (Kalamazoo resident, YWCA)

The Kalamazoo residents were clear in their perspectives that there is a disparity in the occurrence of domestic violence. They strongly believe that “there’s a lot more abuse and, you know, sexual assaults and stuff happening in black families than you will find in the Caucasian families. A lot more.” (Kalamazoo resident, YWCA) It is important to note that in 2011, it was found that the prevalence of intimate partner abuse of high school students did indeed support this claim; prevalence was 4.1% for whites and an almost doubled 7.8% in blacks (Bronson Healthcare, 2013). According to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, 1 in 15 children are exposed to domestic violence every year, and 90% of these children directly witness the violence in their homes (National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, 2015). Additionally, 40% of people who report being abused as a child also report exposure to domestic violence later in life (National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, 2015). Though these studies do not investigate the entire lifespan of each individual involved, these data support the Kalamazoo residents’ assumptions that early childhood experiences with abuse and witnessing domestic violence correlates with exposure to domestic violence in later years.

The racial disparity of domestic violence during pregnancy may also be a contributing factor in the racial disparity of infant mortality because of its indirect and direct impacts on maternal and infant health. For example, a study showed that the risk of severe physical intimate partner violence for female caregivers was almost twice as great for African American women than non-Hispanic white women (Dunbar, 2007). Although infant mortality is a complex and multifaceted subject, domestic violence often plays either an indirect or a direct role in infant mortality. Specifically, 1 in 7 women in the United States that has been abused by an intimate partner results in an injury and over 9 million of these incidents required medical care for the woman (National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, 2015). These injuries can influence an infant’s chance of living before and after birth in many ways: women who suffer from domestic violence are more vulnerable to the contraction of STDs such as HIV and at a greater risk of suffering from depression and suicidal thoughts (National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, 2015).

Perhaps a more direct connection between domestic violence and infant mortality is the impact that the abuse of the mother can have on a fetus is in utero. Intimate partner violence can impact maternal health by increasing their risk of cardiovascular disease, hypertension, chronic pain, gastrointestinal disorders, circulatory conditions, and an increased risk of substance abuse and unhealthy dieting habits, all of which contribute to the infant’s health as well (National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, 2015). Domestic violence also has drastic health effects that impact reproduction and pregnancy such as an increase in disordered eating, gynecological disorders in mothers, and premature birth and low birth weight in infants (National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, 2015). Specifically, preterm birth affected 1 in 9 babies in the United States in 2012, and was the leading cause of infant mortality in 2010, responsible for 35% of all infant deaths (Center for Disease Control, 2013). Overall, it is important that the community of Kalamazoo begins to acknowledge the racial disparity that clearly exists with regard to these issues. Additionally, the Kalamazoo community must initiate driven and direct approaches to confronting this problem. For example, health care providers and support networks of pregnant black women should aim to be more educated, aware, and take initiative to provide the healthiest atmosphere for the mother and her baby. Furthermore, it is essential that the Kalamazoo community recognize the deep interconnectedness of all the aforementioned issues and health effects, in order to more highly prioritize the physical and environmental factors that contribute to the racial disparity in infant mortality.

It is also important to acknowledge the responsibility and grand impact that doctors and hospital workers hold in this issue. In the focus groups conducted, health care workers also recognized domestic violence as a contributing factor in the cases that they see in the hospital. For example, one Medical Social Worker said,

Almost without fail, they have been abused as children, um, sexually, emotionally, and physically. And it’s just constant. But it’s not always sexual, sometimes it will be emotional, and—“Well, I got hit so I’ll go here”—and it just goes on and on. It’s the only interactions they have had with men and how their moms have interacted with them their entire lives, and it’s just what they are used to. And I think that plays a huge piece of what we see with our patients here at the hospital. (Bronson Methodist Hospital)

This indicates that many health care workers who interact with black mothers affected by infant mortality also consider childhood abuse to consistently impact these women throughout their adulthood and, specifically, during pregnancy. Unfortunately, the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence found that, in 2002, only 6% of health care providers consistently screened patients for domestic violence (2015). In light of the numerous and drastic consequences that are possible as a result of domestic violence, health care workers make up an important group of individuals that have a formal, important, and relatively consistent relationship with women before and during their pregnancies. Given that many health care providers interviewed did indeed acknowledge the visibility of domestic violence in patients in the hospital setting, the Kalamazoo community health care providers must aim to increase the screening, education, and supplemental resources available to women in their care.

Nonetheless, it is still crucial to acknowledge that domestic violence is a complex issue that is highly influenced by the victim’s entire upbringing, neighborhood and community. One Medical Social Worker said,

My patients don’t feel safe…Like their answer to a standard question, “Do you feel safe at home?” We are asking that looking for domestic violence and they are like, “No.”…“Well, is someone hurting you?” “Well, no. It’s just not safe. People…there’s guns all over the place; there’s drugs all over the place. I can’t let my kids go outside in the yard and play.” And that’s where they have to live because they don’t have any other options. (Bronson Methodist Hospital)

This quote emphasizes the myriad of deep-rooted and environmental issues at play that all contribute in unique ways to the problems with domestic violence and its impact on infant mortality in Kalamazoo. The ideas highlighted in this paper suggest certain community-wide recommendations that should be made in order to combat the racial disparity in domestic violence in Kalamazoo, in light of its influence on infant mortality. Firstly, the Kalamazoo community needs to raise awareness of the issue and promote open discussion about these issues in terms of racial disparities. Though domestic violence itself is a problem, it is crucial to note the difference that clearly exists between different ethnic groups in order to begin working toward necessary solutions. Additionally, it is imperative that the health care workers not only educate themselves and provide tangible support systems for patients that they see, but to also promote an environment that makes them feel safe and welcome to talk about their personal experiences to help gain trust and motivation to improve each woman’s situation. Similarly, health care providers should be educated on how to more directly and compassionately confront patients about a domestic violent situation and should be required to screen for abuse with every patient they see.

In 2010, infant mortality rates were 5.7 for whites and 19.5 for blacks, indicating that black infants are at least 3.4 times more likely to die before one year of age than white babies (McMichael, 2015). However, in 2015 the risk that black babies would die increased to be 4.5 times greater than that for white babies (McMichael, 2015). Given the widespread knowledge we currently have on the increased health risks, indirect, and direct impacts that domestic violence can have on infant health and mortality, it is crucial that the racial disparity in domestic violence be confronted using community-based approaches. As one black Kalamazoo resident stated, “I honestly feel like it takes a village to raise a child. We need to come together as a community.” (YWCA)