By Mele Makalo

In Kalamazoo, black infant mortality is a pressing issue that demands continued community examination, dialogue, and action. While black infant mortality is not a recent problem in Kalamazoo, the collective community attention towards acknowledging and addressing the issue is. The unfortunate reality that from 2000 – 2012, the county’s mortality rate for white infants was 5.7 deaths per one one thousand births while there were 18.2 deaths per one thousand black infants highlights the critical value of collective community dialogue and engagement in and with the issue of black infant mortality in Kalamazoo.

In recognizing the critical value of assessing and addressing this issue, The YWCA has recent launched the Kalamazoo Infant Mortality Community Action Initiative. The YWCA is a service dedicated to eliminating racism, empowering women and promoting peace, justice, freedom and dignity for all and in fulfilling this mission, the YWCA has committed their programming to further explicating the growing disparity between black and white infant deaths. In partnership with the YWCA, a group of Kalamazoo College student scholars worked on this initiative by gathering data from local community members and health professionals in Kalamazoo through engaging in focus group dialogues.

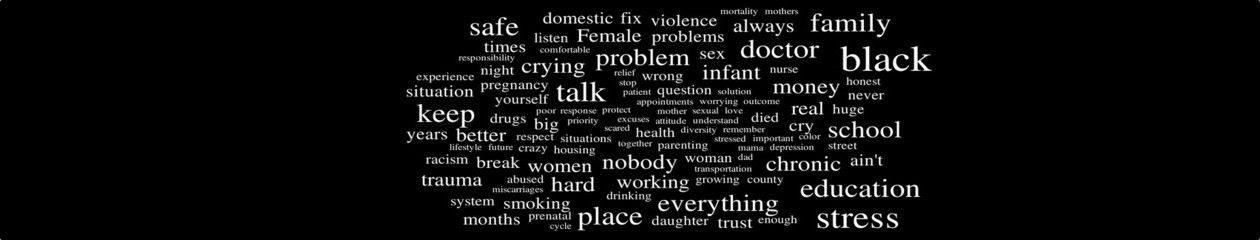

In these focus groups, a theme that came up is that as greater attention has been geared towards exploring contributing factors of black infant mortality, very minimal attention has been tailored towards the impacts of loss and grief of losing an infant. In the focus groups facilitated and organized by the YWCA and Kalamazoo College, there were apparent concerns with regards to the absence of support through grief from mothers in the community as well as a clear misunderstanding of how to handle grief and loss from the health professionals. When recalling and expressing coping with loss of infants, local mothers in the focus groups shared the following:

“Never ask if we need counseling, never, …nothing like that. And us black people really don’t know nothing about it so we, we’re ashamed of it when it comes up with somebody…You’re ashamed when you live in these streets and our, you know, our area, ‘Oh, I’m gonna go see a counselor’.”

“My daughter just turned twenty-five, may she rest in peace, and her day is her day and I think about her every day of my life, especially on her birthday, you know. I’ve still got pictures of my baby. I got her hat. I got her bracelet. I got her certificate of baptism cuz I still got her baptized after the stillborn.”

“People lost infants due to wanting to sleep with their baby. Imagine waking up knowing you slept on your baby. That’s very traumatic.”

“I was like seven and a half months… I knew something was wrong… they didn’t give me any pictures or anything like that at the ultrasound. So they was taking a long time and, um, I went into the hallway and I seen like four doctors out there… they told me, ‘Yeah, he wasn’t breathing. He’s gone.’ They said he died like a week before that and I didn’t know because I still felt him moving and I really don’t want to talk about it.”

Clinicians have direct contact with and responsibility for patients, but in the focus groups as women shared loss of infants, it was apparent that health professionals ability to handle and supporting patients through grief was and continues to be nonexistent. Sidney Zisook and Katherine Shear discuss what health professionals need to know about grief and bereavement. Bereavement is the actual happening of the loss and grief is the emotional, cognitive, functional, and behavioral responses to the death. Zisook and Shear emphasize the importance of recognizing grief as a process as opposed to a state and supporting patients experiencing grief through collaborative and consistent care. While grief is a process that each patient’s experience is unique, there is a form of grief that is paralyzing that interrupts conditions and quality of life. These paralyzing conditions from grief breed psychological and emotional distress that further perpetuates greater risks of women of color under poverty losing their infants and children. The grief from losing an infant combined with grief from racism, poverty, and various forms of oppression put African Americans at greater risk with infant mortality which is what the Kalamazoo County is currently experiencing.

Health professionals in the focus groups recognize that black infants are dying at much higher rates than white infants in Kalamazoo, but struggle to acknowledge how to support patients experiencing grief from institutional oppression and loss as contributing factors to the issue of infant mortality:

“It’s hard, you know, how do you tell what factors lead up to why a child dies? I would say it’s got to be different in every one, and again it’s why does it seem to happen in this group so much more than in another? What’s different about them aside from the color of their skin? You know, and obviously there’s probably some cultural things, but it’s hard to pinpoint what a cultural factor would be that would cause this.”

“Why is it just the African American population that their infant mortality is so high?”

“It sometimes feels like as healthcare providers we’re missing something. It feels like there must be a way to do it better. Because the data is irrefutable.”

“Except when the statistics come out, we find out it’s four times the number of black babies that are dying than white babies. How is that happening?

What’s wrong? What are we missing?”

“That’s the hard part. That’s the puzzle, because we feel like we are giving the same level of care and the same chances and the additional resources and the programs. So why are we still failing? Where are we losing these babies?

The crisis here as Arthur Kleinman notes in The Illness Narratives is the inconsistency between what the patient experiences and what the clinician treats. Through dialogue in the focus groups, it seemed that what health professionals were focusing on was assessing African American culture to discover reasons why black infants are dying at higher rates than white infants as opposed to assessing the culture of oppression in the United States that put African Americans at greater risks of grave disparities that produces grief. If clinicians are focusing on treating individuals as opposed to trying to support and treat patients while also treating the ill institutions such as the medical institution that they are a part of that breeds disparity, clinicians can not properly care for their patients. Racism, classism, and sexism are illnesses that produce symptoms of disparity such as infant mortality, educational inequity, poverty, and domestic abuse. Kleinman refers to illness as something “acting like a sponge, illness soaks up personal and social significance from the world of the sick person.” In recognizing illness as such, this captures the essence of recognizing that people are not necessarily ill, the societies we live in are.

Everyday pains and oppressions are not treatable ills which is why health professionals in the aforementioned quotes expressed confusion and a grave misunderstanding with regards to why African American infants are dying at such high rates in Kalamazoo. Therefore, there needs to be continued dialogue so that everyone can become active culturally competent learners which is the prerequisite to being a culturally competent agent of change. Dialogue is essential because knowledge is not something out there waiting to be discovered. It is a process that rises out of interaction involving dialogue of some sort. Through dialogues, we are provided the opportunity to share our knowledge, challenge our knowledge, enhance our knowledge, and transform our knowledge. Participation in dialogue not only leaves ways for participants to build upon and share knowledge, it provides opportunities to discover our individual identity and develop our worldview. Discovering ones’ own identity does not mean that one works it out in isolation, but to negotiate it through dialogue with others. In doing so, a transformed language is developed in which its discourse exists not for the sake of expression alone but for the sake of the community it makes possible among those who become parties to it. Such dialogue fosters a place of learning in which through conversation, prejudices are tested and meaning is sought out as a way for all participants to become more critical of themselves, their communities, and their role in it. This self awareness and building of consciousness that rises out of dialogue inspires social change.

All in all, dialogue, as being used here is a way of exploring the roots of the many crises that face humanity today. It enables inquiry into, and understanding of, the sorts of processes that fragment and interfere with real communication between individuals, nations and even different parts of the same organization. Dialogue provides ways of identifying and exploring distortions that exist. Dialogue used this way to transform discourse on infant mortality and approaches dedicated towards eradicating the disparity.