By Dylan Shearer

On average in the United States, four million babies are born each year, which translates to approximately 7 or 8 births per minute. A more sobering fact is that not all of these babies will live to see their first birthday; in fact, six infants out of every 1,000 births will die within their first year of life. Surprisingly, in the US more babies die proportionately than countries like France, Germany, England, and even Japan. In this article, I seek to reveal why safe sleep specifically is important by contextualizing it with focus group interviews conducted among mothers and healthcare professionals in Kalamazoo, and I will suggest that safe sleep educational initiatives and a systems integration approach should be utilized to combat infant mortality in a way that builds strong community relationships and fosters communication.

On average in the United States, four million babies are born each year, which translates to approximately 7 or 8 births per minute. A more sobering fact is that not all of these babies will live to see their first birthday. In fact, six infants out of every 1000 births will die within their first year of life. This is termed infant mortality, a public health indicator in which the United States ranks lower than any other developed nation in the world (Reid, 2010). In other words, more of our babies die proportionately than countries like France, Germany, England, and even Japan. In fact, there are even obvious differences in infant mortality by age, race, and ethnicity; for instance, the mortality rate for non-Hispanic black infants is more than twice that of non-Hispanic white infants.

So the question becomes, why are our babies dyeing and why are some at a higher risk than others? What are we doing, or not doing that makes a child more likely to die by the age of one than other developed countries? These are by no means simple questions, and researchers and investigators spend their entire lives dedicated to answering them. Although the topic is very complex, most investigators and public health workers cite sleeping conditions to be an issue at the crux of infant safety, which feeds directly into infant mortality. In this article, I seek to reveal why safe sleep is important by contextualizing it with focus group interviews conducted among mothers and healthcare professionals in Kalamazoo, and I will suggest those educational initiatives and a systems integration approach should be utilized to combat infant mortality in a way that builds relationships and fosters communication.

Fortunately, the overwhelming majority of newborns survive and thrive in early childhood. However, about 3,500 US infants die suddenly and unexpectedly each year. These deaths are diagnosed as sudden infant death syndrom (SIDS). Although the exact causes of death in many of these children cannot be explained, most occur in an environment where the infant is sleeping (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2015). There are two main types of death that occur in the sleeping environment – accidental suffocation and strangulation. Suffocations occurs most often from soft bedding such as pillows or waterbed mattresses, while strangulation can result from an infants head getting caught between railings that are too wide in the crib.

An observation among healthcare professionals is that advertising and consumer products take the focus away from infant safety and place it on comfort and appeals to emotion instead. The “cute factor” is one of the reasons pictures of babies sleeping work in advertisements for a variety of consumer products, but curled up on their sides or lying on their stomachs is not the safest position for sleeping babies (Moon, 2011). During a focus group interview with the Healthy Baby Healthy Start (HBHS) initiative, one employee that frequently works with mothers on safe-sleeping habits voiced this concern and added, “The monopoly and people who are interested in making money off of babies, they put out things that aren’t in agreement with safe sleep and the moms want it because it’s fuzzy and interesting.” Not only are many of these baby products unsafe, but they actually contribute directly to infant death by increasing the chances of accidental suffocation or strangulation.

Perhaps the most significant and difficult obstacle to overcome is communication itself. Kalamazoo is commonly known as being “resource rich” when it comes to fetal and maternal health. This means that there are numerous programs aimed at educating mothers, free services are available, and a large amount funding is present. Yet a theme that became apparent within the focus group interviews was that there is a large disconnect between those providing the services and educational materials to practice safe sleep and those receiving these services.

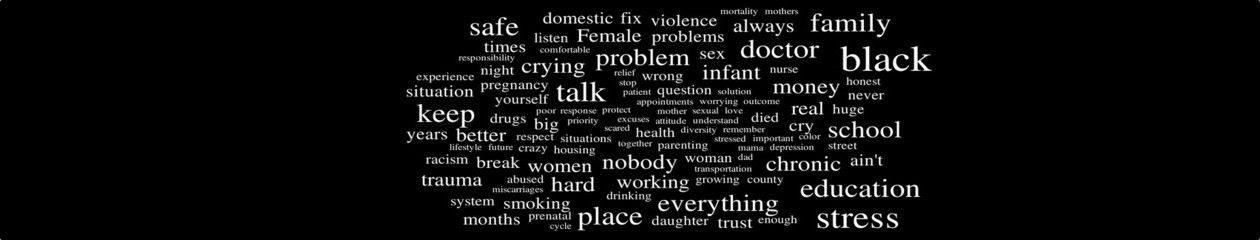

Another observation by healthcare professionals with regard to infant safe sleep was the fact that the medical and residential communities are at odds. A labor and delivery nurse at a local hospital explained, “If I’m telling you how to put your baby back to sleep, about safe sleep, and sleeping in general, but your culture and your community is telling you to do it a different way, how do we make those connections so that I’m giving you information that’s useful to you and not just this story that’s up over here”. On the other end, one mother in a focus group conducted at the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) in Kalamazoo revealed, “They [hospital workers] just send you out the hospital and, [agreement from the group] send you on your way—it’s nothing. Only help you got is the Y and the sexual assault program…And that’s why us African Americans go other places, because there’s nothing out here for us. In Kalamazoo, Michigan we don’t have anything. For us young black mothers who lost kids, we don’t have anything. They don’t help you get over that. I mean, they, they, they don’t. It seems like they just don’t care.” These harrowing quotes truly reveal a powerful message – one that suggests that simply having the tools to practice safe sleep is not enough. There needs to be a more fundamental connection and openness to communication between the healthcare providers and infrastructure and those receiving these services.

To address this disconnect in communication, I recommend that education surrounding safe sleep needs should follow an approach known as systems integration (Frank & Bronheim, 2007). This would require taking the time to think about a mother’s home life as an important piece to forging a bridge over which to communicate effectively. The state of Michigan has actually made a lot of progress in recent years with this approach by spearheading campaigns to address SIDS with initiatives like HBHS in Kalamazoo. Although the foundation has been laid, it has been difficult to reach the heart of communities where infant death and safe sleeping are most problematic. To strengthen communication between providers and mothers receiving services, we need to concentrate on an integrated system of stakeholders, or a broad-based workgroup made up of community members, mothers touched by infant death, as well as the healthcare providers. One mother of color expressed this testament in a focus group conducted at the YWCA saying, “I honestly feel like it takes a village to raise a child. We need to come together more as a community.”

Creating the integrated infrastructure, building trust, enhancing communication, and sharing resources is not a simple task. I believe the outreach needs to begin with the healthcare providers. There needs to be a focus on creating and sustaining culturally and linguistically competent approaches to services and supports to families in Kalamazoo. This would enhance the ability to communicate by leveling the field between those providing and those receiving services. This “whole systems” approach would reach past existing systems that are fragmented and difficult to navigate by involving the public and private sectors to provide a consistent message of maintaining open communications and building relationships (Johnson and Suzanne, 2007). This relationship piece is key and it is primarily why programs such as HBHS in Kalamazoo have seen a lot of success. Feeling connected and worthy of provider investment helps mothers feel more comfortable asking for help or going into the doctor’s office. One employee at the HBHS program expressed in a focus group interview, “In our program, we stay with them until the baby turns 2. You have so much time to build trust here, but in hospitals staff turnover means physicians aren’t there more than a year or 2 so where’s the trust? There’s no relationship because they [mothers] don’t know who they’re going to see.”

The state of Ohio serves as a striking example for the success of this systems integration approach. They have recently jumped to the forefront in the battle against SIDS by working closely with community members as well as providers. They are spearheading many campaigns that target the education of mothers and fathers on infant health and safe sleep, and they require health systems to provide information, support, and bereavement services to families. Ohio has made infant mortality and unsafe sleep a priority.

Ohio has developed what is known as the “Ohio Infant Mortality Reduction Initiative” (OIMRI), which focuses on creating positions known as community health workers (CHW). The goal of this program is to reduce racial disparities among African-Americans in perinatal and infant mortality, and low and very low birth weights. There are currently 14 OIMRI projects located in predominantly urban areas, serving at risk women and infants for poor health outcomes. The CHWs are trained advocates from the targeted community who empower individuals to access family centered community resources through education, out-reach, home visits and referrals. This program really focuses on strengthening relationships with mothers and helping give them the tools and easily accessible education to practices things like safe sleep to reduce SUID and SIDS. The initiative strongly encourages home visits, a piece that crucially builds relationships between providers and families, and is something that is lacking in Kalamazoo. Ohio has enacted statewide marketing campaigns, and works closely with maternal and children’s’ hospitals to develop care that is effective and reaches those most at risk (Ohio Infant Mortality Reduction Initiative, 2015).

I hope this article has brought to light just how important infant and maternal health is and has expressed why it is important to develop educational safe sleep campaigns that involve the community and as well as healthcare providers. The systems integrations approach that I have proposed has proven to be a crucial asset in Ohio, and it has contributed to safe sleep initiatives that focus on building strong and trusting relationships between providers and mothers. Kalamazoo is headed in the right direction, and with a maintained focus on building trust and whole systems integration, we will continue to see decreases in the number of infant deaths resulting from unsafe sleeping conditions.