By Annalise Robinson

In Kalamazoo, black babies are dying at a 4.5 times higher rate than white infants. When we ask the question, “ Why are black babies dying at a higher rate than white?” we must first note that 85 percent of black women giving birth in Kalamazoo County live in poverty. We must then examine the environments in which these mothers and infants reside. Because of the constraints of the segregated neighborhoods, access to adequate health care before, during, and after pregnancies is rare for black mothers in Kalamazoo. Many health and social work professionals in Kalamazoo have named several resources that are available to mothers, but these abundant resources in greater Kalamazoo are not reaching certain communities and neighborhoods for a number of reasons; the inability to access transportation, inadequate family care, and lack of a shared support system of the entire community in the greater Kalamazoo community, to only scratch the surface.

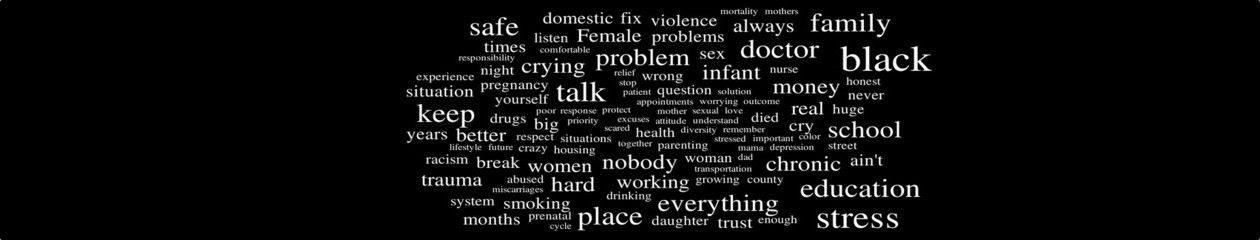

Numerous studies have displayed many social determinants to explain the disparities in the infant mortality rate in Kalamazoo County. A presentation on disparities in infant mortality in Kalamazoo by Arthur R. James MD revealed that some of these social determinants include (but are not limited to): housing issues, chronic stress, lack of family support, poor working conditions, teen births, poor nutrition, under-education, limited access to care, substance use, fatherless households, and neighborhoods. All of these determinants stem from the environment in which mothers and infants are placed. These social determinants explain the fact that black infant mortality is not an issue of the individual, but one that encompasses the entire environment and community in which the individual is present.

Though Kalamazoo holds an abundant amount of resources and organizational support programs for infant mortality initiatives, the resources and support are not technically reaching the high-risk environments in which these mothers and infants reside. Through our focus groups, we have realized that there are an abundant amount of resources for mothers and infants. But in one focus group, it was evident that the resources are not always adequate enough. In that focus group, a social work professional questioned the usefulness of the resources in Kalamazoo: “Do we communicate well with each other? And if people are aware of it [resources], do they access it?” It is clear after talking with community residents, however, that this is not a question of whether the community will or will not access resources, but whether or not the community is able to access resources.

According to a Community Health Needs Assessment of Kalamazoo County (2013), areas that were repeatedly mentioned in focus groups included issues with availability and ease of getting to see a doctor. The data that we have collected in our focus groups prove the same to be true. The following issues stood out: issues with availability and ease of getting to see a doctor; limited specialists who are convenient, especially for certain insurance plans; difficulty with transportation to appointments; challenges with getting timely appointments; and inefficient patient flow that results in lengthy visits.

Inability to access resources can be the result of many things, one main factor being lack of transportation. Because the public transportation system is not very efficient, a pregnant mother could lose an extra hour out of her day just getting to the medical appointment, depending on where she resides. This is time that could have been spent making money at work, preparing food for her family, or caring for the baby in any other way. As a social work professional in Kalamazoo stated: “Well, there are a lot of programs in Kalamazoo that do help moms during pregnancy and then after they have a baby—I mean I think Kalamazoo is pretty healthy community as far as that goes—resource rich… some problems with moms doing that is, you know, transportation to and from, time availability, or understanding the importance of staying connected with those resources for them.” Another social work professional stated: As a medical social worker stated, “…getting transportation I think is a big issue for a lot of pregnant women. Housing … so then if they aren’t making it to the prenatal appointments, they aren’t getting a lot of the education and sometimes do have poor pregnancy outcomes as a result of that, unfortunately.” Lack of access to essential appointments means less care that the infant and mother are receiving. This specific transportation barrier is a result of many constraints, one of the most obvious being placement of the mother in relation to professional services. Lack of time to take at an appointment is also connected to the mother’s availability to leave the home. If a pregnant mother already has one or more children in the home, she is expected to balance caring for her children, her own well being, her work, and making it to appointments.

Another reason hindering the community residents to utilize resources from professionals is lack of knowledge about them. According to social work professionals, depending on the type of neighborhood and what kind of community that these mothers are surrounded by, knowledge about certain resources can be nonexistent. For instance, a social work professional remarked on the reasons that a mother did not utilize available resources: “…it’s generation to generation. Young mom, her mom was young mom, her grandma is young. And so she made it sound like in their families, they don’t do that [go to appointments].” In this certain focus group, there was a sentiment that generational ties in the community are often stronger than those of professionals in Kalamazoo; therefore mothers are more likely to listen to their mothers, who listened to their mothers, and so on. Along with the chronic stress of everyday living and the inability to reach the resources outside of the neighborhoods and communities, the health and social work professionals in this focus group agreed that the lack of utilization of resources stems from the ignorance of family members in their community.

But Kalamazoo community residents propose a conflicting view. According to a community resident, “…you gotta hear it [resources] through the grapevine, some programs I just find out about them like where did that program come from, I never heard of it, it’s like sometime you gotta hear it through the grape vine.” This means that the lack of knowledge about the resources and available programs is not simply a “generational” issue in the Kalamazoo community. This lack of knowledge reflects the miscommunication and disconnect between health and social work professionals and the Kalamazoo community residents. There may be an abundant amount of resources coming from these professionals that support mothers and infants— but are these resources reaching the neighborhoods and communities that need them the most?

Among the diverse twenty-two neighborhoods in Kalamazoo, three neighborhoods stood out with the highest rates of poor birth outcomes from 2008 to 20011: Eastside, Edison, and Northside neighborhoods. These neighborhoods have the highest amount of black people living below the poverty line in Kalamazoo. (HDReAM Online Data Mapper). It is known that poverty, lack of or low levels of education, and low social status of women in many societies seriously constrains the access of women to certain health services. (Women’s Health). Poverty has proven to be a main factor in the determinants of black infant mortality in Kalamazoo for many reasons: the main reason is the lack of time for and mode of transportation to medical appointments.

During our focus group process, it became evident that most of the social work and health professionals were well aware of the social barriers that these mothers face on a day-to-day basis. In neighborhoods represented by zip codes 49001, 49007, and 49048, nearly 26 out of every 1,000 black babies born do not live to be a year old. (Bronson, 2013). Some social work and medical professionals whom we interviewed in focus groups were well aware of this data about the zip codes and underlined the importance of entering these specific communities: “…I think it’s getting in those zip codes where we are having them [infant deaths] and getting in there with those people…” But it is evident from the lack of communication from the professionals to the community that this specific community intervention is not yet being implemented. One health professional remarked: “We still are in our own silos and we are not getting into those homes and into those heads where we need to be getting.” The glaringly obvious barrier between the professionals in Kalamazoo and community residents in local neighborhoods could at least begin to collapse with the implementation of more required cultural competency and humility courses. It is evident that this kind of cultural training could be of use to health professionals through this statement by a health professional: “in our community if you take a look at the other programs they don’t really culturally represent the community that they’re trying to serve. Their heart is probably there but it’s not the diversity that is needed in the home visitation group to represent high-risk groups.”

Another way in which we might be able to lower the disparity of black infant mortality could be the development of more home-visitation programs. Although such visitation programs exist today, the Kalamazoo community and neighborhoods would benefit greatly with more of these interactive programs. There are certain programs already in place that benefit mothers in certain neighborhoods by transporting them to and from appointments as well as delivering physical resources to the community, such as safe cribs or car seats. But there must be more of these programs ready to assist in the actual neighborhoods and communities.

In a focus group with community residents, one person stated, “More people in the community have to get involved, that’s all it is.” The community is calling for action. The blame should not solely be on the mothers to take care of their children. This issue of black infant mortality in Kalamazoo is systemic and must be worked on at the community level. The term “community involvement” should also not be looked at merely from those inside the neighborhoods where black infant mortality is most prevalent. According to Baffour and Chonody (2009), in order to address the “nested arrangement of behavioral and environmental determinants of health,” we must “assist in developing community-based instead of community-placed practice and policy strategies….thus, the target of intervention is not only the individual, but proximal targets including social institutions that impact health. The responsibility should not only be placed in the hands of the neighborhoods and communities in which black infant mortality is most highly concentrated; rather, it should go beyond the barriers of these areas and should be shared with the health care and social work professionals of the greater Kalamazoo Community.